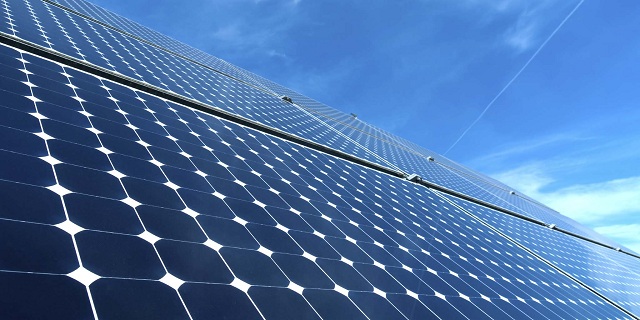

Things can change very quickly in the solar industry, and no more so than when new trade-related cases are introduced or existing ones are amended in scope. Often companies – and in particular module suppliers relying on export revenues – suddenly find themselves with a golden opportunity that was previously not in their strategies, or have barriers unlocked that remove competitors based in other countries.

This article explains why ‘Made-in-India’ solar PV module manufacturers could end up seeing immediate opportunities to export to the lucrative US and European end-markets, if certain trade cases come out in their favour; and if downstream EPCs/developers and investors are convinced that the quality and reliability of the modules on offer are at the level they demand to mitigate against potential on-site underperformance and maximize investment returns.

The article will also explain how a dedicated session at the forthcoming PV ModuleTech 2017 event in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, on 7-8 November 2017, will seek to reveal the leading Indian module manufacturers that are expected to be among the key beneficiaries should the trade cases move in the favour of India, and what needs to be done to gain global supply acceptance.

A quick review of Made-in-India module manufacturing

Of all the major countries where cell and module manufacturing is active today in GW-level volumes, India has by far the longest history, with the country being one of the first to embrace solar as a technology more than 30 years ago.

The collaboration between Tata and BP-Solar in Bangalore was at its time ground-breaking in the PV industry, and benefited in the day from BP-Solar having an R&D obsession that was matched only by the fervour seen in Japan from the likes of Sharp, Sanyo and Kyocera.

Furthermore, prior to the solar industry having its first growth-spurt phases in Japan (before the current Fukushima-incident driven boom-phase) and Europe (Spain, Germany, Italy), other Indian government-controlled conglomerates had set up somewhat skunkworks-based cell and module production lines, some of which still exist today albeit it in a rather dormant state.

However, it was during the European-driven solar industry growth phase of the mid-2000’s that saw the biggest advancement within India from a fab manufacturing standpoint, with the construction of state-of-the-art facilities using imported process equipment from the leading tool makers in Europe and especially Germany.

The focus was largely on pure-play cell manufacturing at the time, and by the time the factories were operational, manufacturers were confronted by the GW juggernaut of cell and module capacity that had been built up almost overnight across China and Taiwan.

Taiwan chose the pure-play cell route, as opposed to the ‘anything c-Si’ route that was China, and for the next few years, no-one anywhere could compete with cell production quality, cost and volumes that were coming out of Taiwan to a (then) tariff-free solar world.

This ushered in a phase of inactivity within India that was to last until recent years during which the domestic end-market reached multi-GW level as one of the leading global demand countries serving as a long-term growth target for most of the leading international module suppliers.

Modules have come into India in droves from China, and ASPs have been firmly at the bottom of global tables during this period; two factors that make relying upon the domestic market both challenging from a profitability standpoint and frustrating in light of the end-market status and growth metrics.

In this time, only a couple of Indian module manufacturers have succeeded in having any meaningful levels of overseas shipments, and the sheer volume of deployment in the country has also propelled the existence of new module producers that are sufficiently connected with downstream project deployment.

This year, Adani hit the global manufacturing headlines, with its GW-scale cell/module fab in Mundra; 2018 will however be the year that the industry sees how much Adani has succeeded in both its ambitious ramp-up plans and its ability to have strong overseas module shipment levels.

The wildcard trade-based upside to Indian export prospects in 2018

If the Section 201 case in the US does come to fruition, and results in a geographic shakeup in terms of the countries that are able to import into the US and be excluded from any tariff or minimum price requirements, then things could get interesting for Indian module suppliers that have global presence.

Add to this the prospect of both cells and modules being produced in India (that remains one of the very few countries still to have meaningful capacities for both cells and modules), and things could get even more exciting for Made-in-India brands.

In Europe, a new MIP has now come into force, and the full implications are certainly still being understood, with more than one interpretation of what this means for product shipping from countries in Southeast Asia, including Malaysia and Thailand.

Given that much of the supply to Europe had been diverted to these Southeast Asia countries following the implementation of the original MIP ruling, this clearly leaves a gap that would certainly see Indian module exports (assuming they have the correct source of cells) being in greater demand.

While there are many questions yet to be flushed out, there is every chance that 2018 could become a year that Indian module suppliers need to become much more export-savvy, and seek out the potential upside opportunity that may unfold very quickly.

Made-in-India quality and bankability: is the global downstream segment aware?

Scrutiny on module supply for utility-scale solar outside India is much more rigorous than in the domestic market currently, and for Indian module manufacturers to gain traction globally from 2018 onwards, the global downstream stakeholders will certainly be hard at work doing factory audits, due-diligence reporting, and bankability analysis to ascertain which companies and module technologies meet all the demands from banks and investors bringing in the site-related finances.

These fundamental issues have driven us to incorporate a dedicated session at the forthcoming PV ModuleTech 2017 conference in Malaysia on 7-8 November:

• Made-in-India modules for global Industry deployment: understanding the key suppliers, technologies and product availability.

India’s Ministry of New & Renewable Energy National Solar Mission Division currently states that there are almost 120 module manufacturers within India. Of these, only 20 have operational capacity that could in theory deliver supply levels overseas that could be considered viable for large-scale deployment.

Within this group of 20, less than half are in a position – or have the desire – to commit fully to being viable module suppliers outside India.

However, it only needs half a dozen or so module suppliers in the 300MW to 1GW bracket to emerge as a credible subset of Indian module suppliers for exporting to the US and European markets, and potentially we have 3-4GW of modules that would be more than sufficient to meet any potential shortfall in supply to key markets such as the US in 2018.

But who are these Indian module manufacturers? What supply levels could they allocate to overseas markets? What type of technologies are they incorporating into their module portfolios? How are these module suppliers gaining third-party certification? Which (international) independent engineering firms have experience in dealing with these company’s product offerings?

Source: https://www.pv-tech.org/editors-blog/why-2018-could-be-a-breakthrough-year-for-made-in-india-module-exports