Scientists have spoken collectively and their message is loud and clear: Act now to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial times or abandon billions of people to suffer the social and natural dangers of a hotter planet. It’s now over to governments to slow down warming.

As a relatively poor country, India will be among those most adversely affected if warming exceeds 1.5ºC. Along with the rest of the world, India will have to radically transform the economy – something akin to a “green, white, telecom and IT revolution all rolled into one.”

Experts say India is already taking action, but it needs to step up the scale and speed of its efforts.

“The window of opportunity for action is much smaller,” said Priyadarshi Shukla, chair of the Global Centre for Environment and Energy at Ahmedabad University.

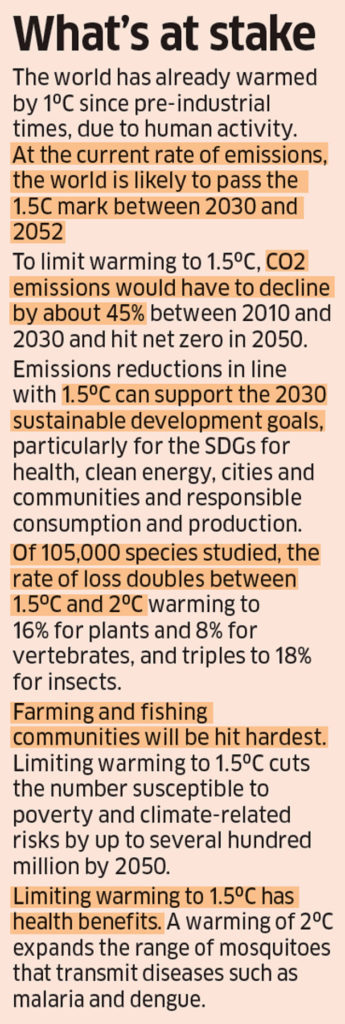

In its report, ‘Global Warming at 1.5ºC,’ released on Monday, the UNbacked Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said time was running out to avert the more disastrous impacts of climate change. The global average temperature is already 1º C above pre-industrial times and, at the current rate of emissions, the earth is warming up 0.2ºC every decade.

“Every half-degree of warming matters,” said Hoesung Lee, the chair of the IPCC.

India has already experienced weather changes in Uttarakhand, Chennai, Srinagar and, more recently, Kerala. The heat waves of the past summer and the uneven rainfall, with floods affecting some regions and very severe drought conditions in others herald a huge and expanding danger.

“We have a generation or less to make some dramatic changes in the way that economies run, the way we govern our systems,” said Aromar Revi, coordinating lead author of the 2018 IPCC special report. Changes will be required across energy, transportation, urban and agriculture systems.

However, like other experts, Revi stressed that this is also a moment of opportunity for India. He argued that at the per capita level, because of our large population, India is not a significant emitter. This gives India a chance to rework its entire energy system and the way agriculture, water and the cities are managed.

“It is a moment to do the things we haven’t been forced to do before,” said Revi.

India has an ambitious programme focused on increasing its renewable energy generation capacity, but the pace needs to accelerate.

“It needs to maintain momentum there by ensuring that targets are met and raised, that contracts are honoured, transmission losses reduced and attention is paid to technology development and manufacturing,” said Arunabha Ghosh, CEO of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

The key is in grid stabilisation and the pace at which renewable energy generation is scaled up.

“Grid stabilisation will need to be addressed in a systematic way, particularly the question of balancing renewable power in the grid as the power system will increasingly depend on variable renewable sources. What is ultimately required is a paradigm shift in financial and operational systems,” explained Thomas Spencer, a research fellow at The Energy and Resources Institute in New Delhi.

Ghosh pointed to energy efficiency as an important segment to drive radical transformation.

“The early gains on energy efficiency in large industry should be supplemented with better enforcement of industrial emission standards,” Ghosh said.

While independent assessments show India is on a path that’s in keeping with a 2ºC rise, experts say that given the current trends in renewable energy deployment, it’s likely that India will surpass its 2022 goals.

g2

“India will not only meet the 2ºC but is likely to do more than its required levels to keep warming to less than the 2ºC,” said Srinivas Krishnaswamy, CEO of Vasudha Foundation. “India can do more in order to be in line with the 1.5ºC goal.”

Krishnaswamy, a veteran of climate change negotiations, said India must focus on implementing its targets – whether it’s renewable energy, electric mobility or energy efficiency.

He said the focus must be on “putting in place the infrastructure such as electricity transmission and distribution infrastructure, electric charging stations for e-vehicles, fast track and ensure strengthened public transportation systems and importantly, address the issue of access to low-cost storage solutions.”

“The solutions required to limit warming to 1.5ºC are available. What is required is to speed and scale up implementation. Governments have to review targets with 1.5ºC in mind rather than 2ºC,” said Shukla of Ahmedabad University who also chairs the IPCC Working Group III on mitigation.

Implementation is often “fragmented,” according to Minal Pathak, a professor at the university’s Global Centre for Environment and Energy. “Take Ahmedabad’s heat action plan. One question is how can you take this plan to other cities? And the other issue is how do you give the plan a long-term focus?”

Pathak said what is required is policy coherence – the political will to take the message from science and translate it into actionable policy is crucial.

“A lot more work needs to be done to take national policies and implement them at the local level such as cities,” she said.

As Shukla put it, “The scientists have done their homework, the scientific evidence is clear. It is now for governments to act.”